Project Summary:

I am currently the software lead for Rocket team at UCSC. Our team recently competed in the NASA University Student launch initiative where we designed and built an 11 foot tall L2. As the software lead I developed the control system for our variable drag system, AKA airbrakes, incorporated into the rocket. Unfortunately due to weather restrictions our team was not able to complete a final launch. Although we couldn’t launch the system our airbrake system was completed and as a verification process I decided to create an “Iron Bird” system for testing, in which the system is pulled apart and fed data to emulate a launch to observe the system reactions.

Design Process:

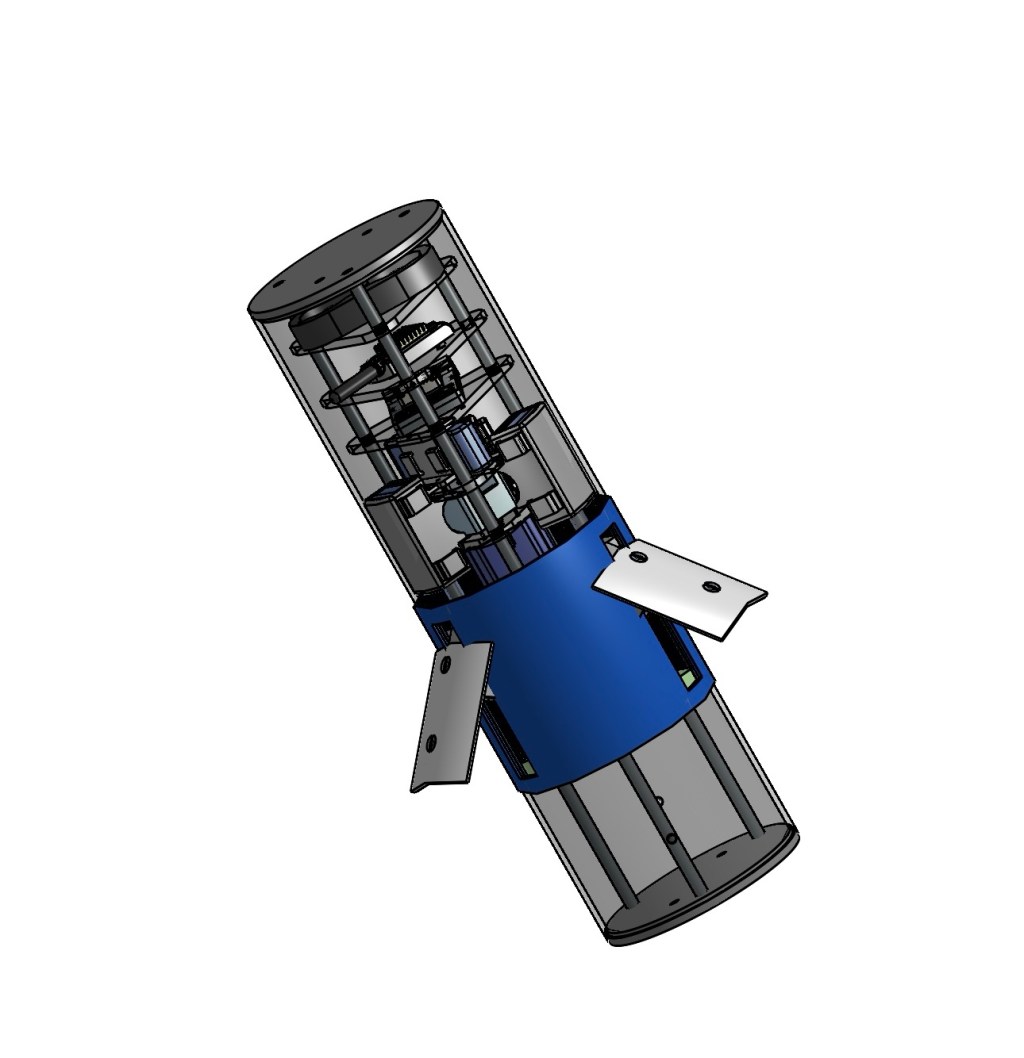

Thanks to several robotics engineer majors on our team, I did not have to design the mechanical portion of the airbrakes, and was able to solely work on the software portion of the design. Our imu and avionics system was an off the shelf product called the Pixhawk. The Pixhawk is an open source drone stack that has all of the IMU sensors we required while also providing customizability to do its open source nature and i/o pins.

For repurposing the pixhawk system to our airbrakes we created our own fork of the company github repository and rebuilding the code system from scratch utilizing some of the prebuilt API hardware. In order to build the Airbrakes system I needed to tackle three challenges:

- Verification of data

- Accurate prediction of apogee

- Control system to determine changes to achieve correct apogee

- Actuating the Airbrakes via PWM

Data Handling

In a perfect world our IMUs wouldn’t need any data verification, but based on the Pixhawk specifications I knew before hand that sensors like the accelerometer weren’t rated for the Gs our motor was outputting. This resulting in accelleration clipping in the raw data. My method for most of the sensors was to approach by creating a queue that I can average to have a rough estimate of current velocity or acceleration for each vector.

Control System

Ignoring a full deployment approach that I don’t feel is interesting enough, the first approach I researched was calculating the drag coefficient for each position available for the airbrakes. Using this I could determine the apogee with drag coefficient equations

Problems:

- Costly to determine drag coeffiecent for each positions and each velocity with simulations

- Did not have a powerful enough computer and outsourcing would burn through budget

- Drag coefficient equations were complicated to utilize on the pixhawk during flight.

- Orientation and other factors during flight could make any drag coefficient calculations innaccurate.

Secondly there is the option of comparing an ideal flight simulation to the current flight to determine whether the rocket should be slowed down, which would rely mostly on altimeter data. This would occur during the coasting phases to determine if the current altitude and acceleration curve matches the simulated rocket one, and adjusting to match if not.

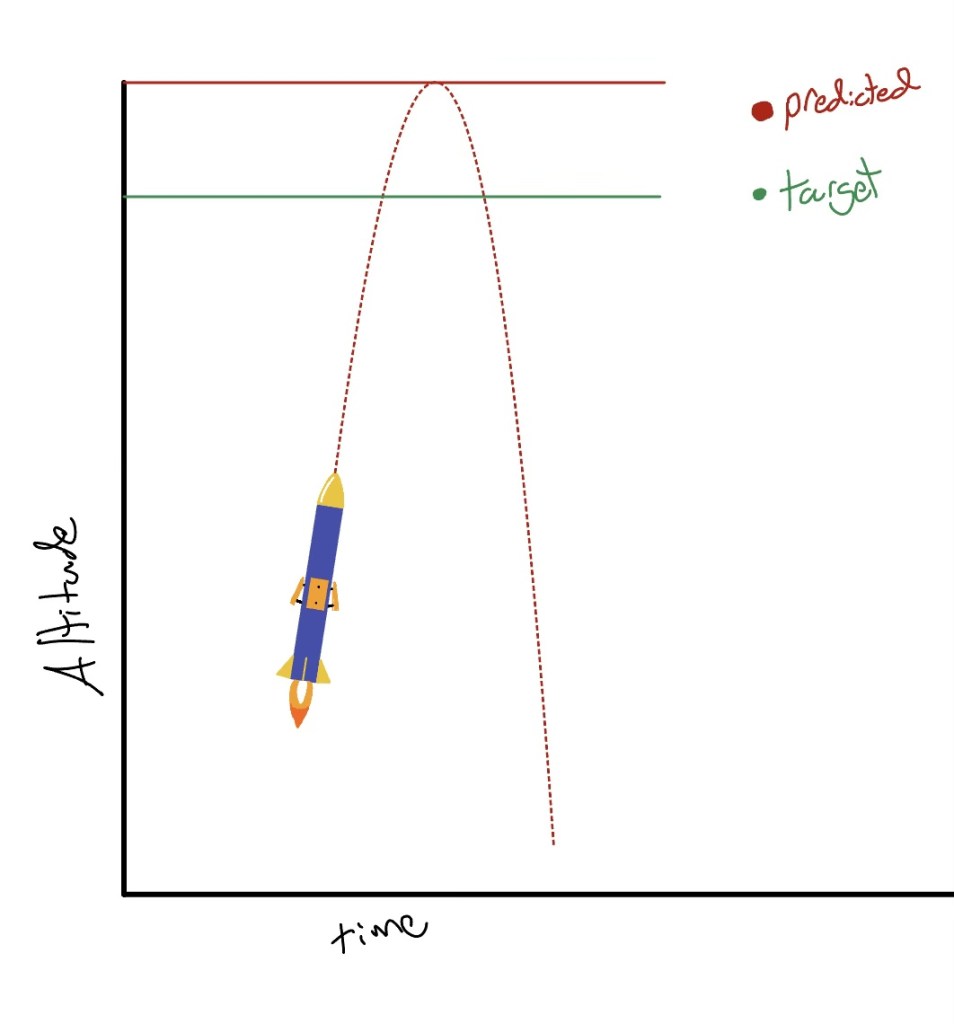

Lastly, the control system I decided on was to calculate the final apogee based upon our current Z acceleration. This relies upon accurate acceleration data, and even though we mentioned acceleration clipping previously there is no such problem during our coasting phase after burnout. This would essentially mean using our current Z acceleration and current altitude we can fairly accurately determine the final apogee, and if overshooting actuating the airbrakes open until our acceleration creates the correct apogee.

Regardless of each situation the control system needed to have an arming stage, a motor burnout detection stage, the deployment phase during coasting, and to close after apogee is hit to protect the flaps during landing.

Programming

To program the rocket and implement our control system wasn’t too difficult. Once I had understood the Pixhawk architecture and could implement my own programs the logic behind it wasn’t too difficult. Made in C, the control software using some I/O api to send PWM values to a stepper motor controller. Once the PWM value bounds were set the angle of deployment would be determined by using the percentage between those two outerbounds. First to implement was the data verification process used to swap between states during the flight. Motor burnout was detected when acceleration was no long positive from rocket thrust and acceleration towards the grown began. Once deployment phase began the previously discussed acceleration based logic system takes place. and Finally once we could determine apogee was reached the final apogee would be saved in a seperate file to the sd card and the Airbrakes would close.

Testing

Initial assembly of the airbrakes system was simple and testing its capabilities came down to attaching weights with a wooden frame to make sure it could handle any drag foreseeable during launch, which it could.

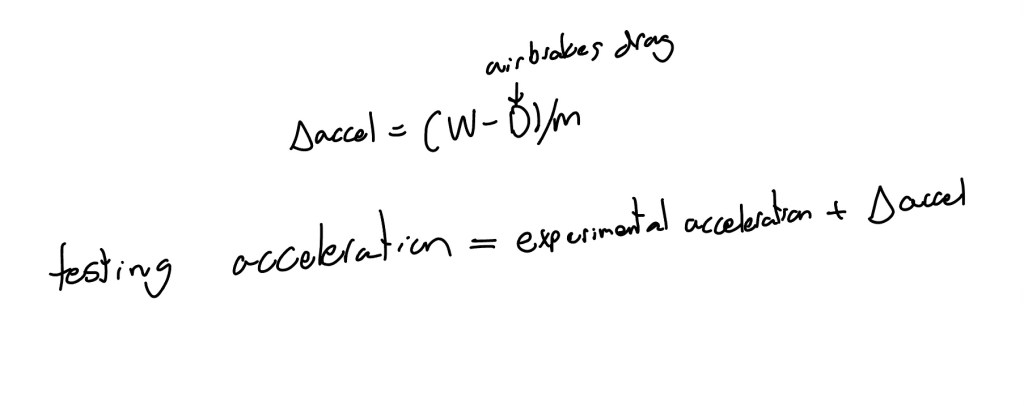

One main issue we faced occurred when weather restricted our launch dates and we had to pullout of the competition. This meant the airbrakes system could not be field tested. I still wanted to test in someway so I was inspired by Joby Aviation from a visit to their testings sites and tried to emulate an Iron bird system. This meant that I took previous flight data and would overwrite the onboard sensor API with my own API that pulled and fed data from CSV files recorded on an actual launch. Where this system is lacking is in adapting the velocity/acceleration data when my airbrakes responded. I’m sure that some factors I wasn’t aware of meant the acceleration data wasn’t adjusted realistically based on different levels of deployment, and I can’t prove that until a real launch.

My solution was to use the drag coeffiecents we determined for each airbrakes flaps and to determine the acceleration/velocity effect it would have. The previous data from the rocket with no airbrakes on it already had a close to realistic drag coefficent of a rocket with closed airbrakes. This meant I could simply determine the drag force of the airbrakes independently of the full rocket and add the resulting acceleration change as a new factor in my current acceleration data to create as close to realistic as I could manage.

Conclusion/Improvements

Overall I was pretty happy with the system given time restraints and budget capabilities. Unfortunate situations like the weather restricting flight testing are out of my control and the choices I made in response were ones I think showed ingenuity and I believe I will use again as a form of testing for other projects.

Improvements:

- The calculations I used for the Iron bird system could have been implemented into the control system. I initially couldn’t simulate the drag coefficient of the whole rocket with airbrakes at each position but forgot that drag force was cumulative and by simulating the airbrakes flaps on their own my control system could be more accurate than relying solely on acceleration predictions

- A real flight test if given another chance to launch would prove any of my systems

- There were restrictions within the Pixhawk system and things like accel clipping or broken API has pushed me to start working on my own flight controller for future rockets

- On a perfect system I would also compare the current data with a simulated launch to flag irregular data so it will be easier to review the data afterwards.